In 1961 Fausta Cialente published the novel Ballata levantina with me in the lead. She did not really consider that becoming public might wake my desire to leave the novel altogether. For a start I found myself on shelves of libraries, then stored in dark archives.

If readers can borrow me with the novel, I thought, I should be able to borrow myself and walk out. I had to find Isabel. She is the one who translated me into English, making me one of The Levantines, as she titled the novel’s translation. I was curious to find out what it takes to lead a translated life.

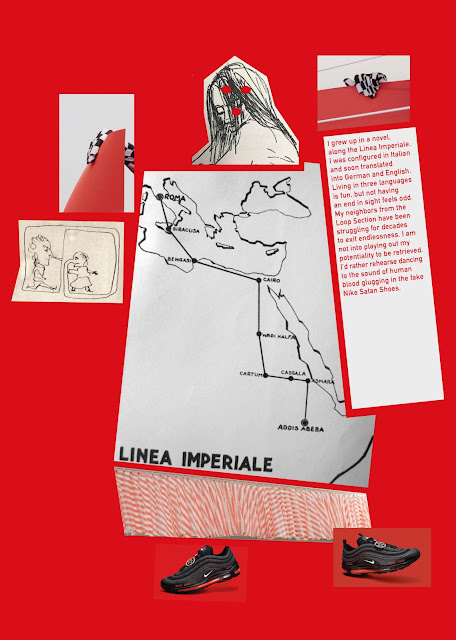

Soon I learned that life outside the archive was governed by stricter linearity than in the memory Fausta configured me with. She neither equipped me with a pure bloodline, nor with a language lineage or a passport with a line for nationality, which seem so indispensable both in and out of the archive. To flee these lines, I began borrowing segments of them, thus breaking their alleged continuity, and reassembling my discontinuous self.

The business of borrowing got me roped in the free-for-alls of cultural appropriation, pushing me again and again into some dark place of origin I never possessed. As if the revolt of appropriation art never happened. The thing is, you can borrow lines but unlike books you can’t return them. And I need to borrow lines endlessly, since reassembling myself never really ends. Not even by death, an invention that wasn’t tailored for us printed characters. We might die at the end of a novel, but we live again once you turn its pages back to the beginning.

If only one could collect lines, I would set up a library, but most lines rarely show, especially lines of flight tend to disappear the moment they are drawn.

Eran Schaerf

Levantine Line Library

February 26 - May 21 2022

Opening February 26, 16 - 19 h.

Open on Saturdays, 15 - 18 h.

A.VE.NU.DE.JET.TE - Institut de Carton vzw

Avenue de Jette 41

1081 Koekelberg / Brussels

10 min walk Metro Simonis / Elisabeth